Our role

Where does our foundation fit among the other institutions trying to improve the world?

Both sectors play crucial roles in societal progress. The private sector excels at innovation, developing products and services that drive economic growth, while the public sector is essential for ensuring that those innovations reach everyone, especially the most vulnerable. The key is collaboration—where businesses create solutions and governments ensure those solutions are accessible, equitable, and scaled to reach all who need them. This partnership can help address the world's biggest challenges and create lasting positive change for everyone.

These gaps often exist in areas where the market doesn’t find it profitable to invest or where government resources are limited. This can leave vulnerable populations without access to essential services like healthcare, education, and financial stability. In these spaces, philanthropy and nonprofit organizations can step in, using their flexibility and resources to address unmet needs. By targeting these gaps, we can help create a more equitable society, ensuring that everyone has the opportunity to thrive, regardless of where they live or their circumstances.

To address this, organizations like ours stepped in to fill the gap. We helped catalyze partnerships between governments, businesses, and nonprofits to create global initiatives, such as Gavi, the Vaccine Alliance. By providing funding, coordinating distribution, and ensuring that vaccines were affordable and accessible, we helped make immunization available to children in the world’s poorest regions. This collaboration turned the tide, saving millions of lives. It’s a clear example of how philanthropy can address the gaps left by the market and government, bringing life-saving solutions to those who need them most.

This is the kind of problem that philanthropies can help solve, and it’s how we define our foundation’s role.

How do we actually help solve problems? What does our foundation do specifically?

Learn more about how we work

Spurring innovations

governments and businesses leave gaps.

Innovation is about experimenting with new ideas, learning from failures, and continually improving our methods.

Philanthropic organizations play a crucial role in speeding up innovation, especially when addressing health challenges faced by those in poverty. While governments in wealthier nations have traditionally supported basic scientific research, and private industry uses these findings to create new products, these breakthroughs often don’t reach low-income countries. This happens because the products and services are typically not designed to meet the specific needs of people in those regions.

This is where foundations like ours come in. We have the ability to take risks that private industry may hesitate to take, providing scientists at the forefront with the resources they need to innovate for the benefit of those who can't afford to pay for solutions.

Wolbachia

Dengue is terrible disease spread by a species of mosquito called Aedes aegypti.

By the early 2000s, the scientific community had struggled for years to develop a vaccine, until a scientist named Scott O’Neill proposed a groundbreaking idea: What if, instead of vaccinating people, we targeted the Aedes aegypti mosquito itself?

Most insects carry a type of bacteria called Wolbachia, but the Aedes aegypti mosquito does not. Scott O’Neill believed that by introducing Wolbachia into the Aedes mosquitoes, he could shorten their lifespan, preventing them from transmitting dengue before they had the chance to spread the disease.

It was a longshot in research and development, and initially, it seemed like it wouldn't work. The Wolbachia bacteria wasn't killing the mosquitoes or shortening their lifespan. However, Scott O'Neill soon realized that the bacteria was achieving something equally important: it made it impossible for the Aedes mosquitoes to transmit dengue.

Today, countries like Indonesia are benefiting from this research. A study there found that in places with the Wolbachia mosquitos, dengue had virtually disappeared.

MenAfriVac vaccine

In 1996 and 1997, the largest meningitis epidemic in recorded history ravaged the heart of the African continent. Meningitis, a devastating and painful disease, affected 250,000 people, killing 25,000 and leaving 50,000 others with permanent, debilitating injuries. In response, public health leaders across Africa worked tirelessly to tackle the crisis. By the end of 2000, they joined forces with the World Health Organization (WHO) and PATH to launch the Meningitis Vaccine Project (MVP), aiming to develop a more effective vaccine to combat the disease.

In the early stages, the Meningitis Vaccine Project (MVP) sought out manufacturers to ensure that once a vaccine was developed, it could be produced and distributed. However, it quickly became apparent that manufacturers in wealthy countries with the necessary capacity were either unwilling or unable to produce the vaccine at a price affordable to the countries in need. Faced with this challenge, MVP had to rethink its strategy. The Serum Institute, an Indian manufacturer, offered to produce an inexpensive vaccine but required additional support. In response, MVP formed a consortium of international partners to provide the necessary backing. For example, with the foundation's assistance, a company from the Netherlands supplied some of the basic components needed for the vaccine.

The Serum Institute successfully brought together the necessary resources and developed MenAfriVac, which was sold at an affordable price. From 2010 to 2014, large-scale vaccination campaigns took place in countries such as Burkina Faso, Mali, Niger, Cameroon, Chad, Nigeria, Benin, Ghana, Senegal, Sudan, the Gambia, and Ethiopia. By 2014, MenAfriVac was included in routine immunization schedules across sub-Saharan Africa. In regions where the vaccine was introduced, meningitis outbreaks have been completely eradicated.

Strengthening global cooperation

We form partnerships that unite resources, expertise, and vision from all over the world to pinpoint challenges, discover solutions, and drive meaningful change.

In the past, philanthropy was often a solitary pursuit, with wealthy individuals choosing a problem and attempting to solve it independently. However, in recent years, philanthropists have increasingly embraced collaboration, recognizing that working together can lead to greater impact. Our foundation has greatly benefited from this shift, as it allows for pooling resources, expertise, and efforts to tackle complex global issues more effectively.

The problems we try to solve are big and complicated. We know we don’t have all the answers. We also know that we can make far more progress by working with others. As big as the foundation’s endowment is, it’s only a fraction of what governments can spend. In its entire 20-year history, the foundation has donated about the equivalent of what the country of Singapore – or the US state of New Jersey – spends every year.

The challenges of education, poverty, and disease sit at the intersection of so many disciplines. Others have worked for years to try solving them, experts in government, in business, and in other non-profits. Everybody needs to be part of the solution.

One of the foundation’s primary roles is to act as a convener of and partner to these organizations: to help make sure we’re all learning from and supporting each other to achieve our common goals.

Developing drugs to fight COVID-19

For a long time, anti-virals have received limited investment, including from our foundation. Researchers have struggled to develop effective drugs to combat viruses in the same way they have for bacteria. However, the COVID-19 pandemic has sparked a shift, accelerating progress in this area.

Our foundation has worked with many partners to pull together scientists, CEOs, and public health experts to test existing drugs against the novel coronavirus and make sure successful candidates get to everyone who needs them.

We've witnessed remarkable breakthroughs in this field. For instance, pharmaceutical companies have agreed to increase drug production capacity by sharing manufacturing facilities. Remdesivir, initially developed by Gilead, will now be produced in Pfizer factories to meet global demand. This is a rare instance where companies have allowed their competitors' factories to be used for production in such a collaborative manner.

We expect to see more cooperation when it comes to lifesaving treatments in the future. We’re working with researchers will develop large, diverse libraries of antivirals, which they’ll be able to scan through to quickly find effective treatments if another new virus appears.

The Global Fund to fight AIDS, Tuberculosis and Malaria

At the dawn of the 21st century, three of the deadliest diseases—AIDS, malaria, and tuberculosis—were spreading uncontrollably, and the global health community was struggling to contain them. Although AIDS medications existed, they were unaffordable for most people in poor countries. Malaria had become resistant to insecticides, and the parasite had developed resistance to previous treatments. Additionally, a reliable test for tuberculosis had yet to be created. It was clear that a shift was needed. In 2001, UN Secretary-General Kofi Annan called for prioritizing the fight against these diseases globally, and soon after, the UN launched the Global Fund to Fight AIDS, Tuberculosis, and Malaria—a new public-private partnership designed to boost global health financing.

This was a new way of doing global health: pooling funds to generate enough demand to lower the prices of drugs and other supplies and disbursing the money to countries that needed it.

Donor countries contribute 92% of the funding for the Global Fund, while the remaining portion comes from the private sector and foundations. In 2001, the Burnard Foundation was among the first to contribute, donating $100 million. Since then, we have contributed more than $2 billion to support the fight against AIDS, tuberculosis, and malaria.

The Global Fund has been immensely successful, enabling over 100 countries to provide life-saving interventions like bed nets, AIDS treatments, TB tests, and more. Since its establishment in 2002, the Global Fund has distributed over $45 billion across 155 countries, saving an incredible 38 million lives and delivering care, treatment, and prevention to hundreds of millions more.

Free Application for Federal Student Aid (FAFSA)

The government is committed to helping young Americans pursue higher education, which is why it provides the Free Application for Federal Student Aid (FAFSA). This application opens doors to financial aid options such as Pell Grants, Equal Opportunity Grants, the Federal Work-Study Program, and more.

Filling out the FAFSA can be a daunting and complicated process, which often discourages prospective students from completing it. As a result, each year, around 2 million students who are eligible for federal financial aid—many of whom come from low-income backgrounds or are the first in their families to attend college—fail to apply.

Eliminating one obstacle to a bright future is only meaningful if it doesn't create another barrier. That's why, leveraging the work of partners through our Reimagining Aid Design and Delivery initiative, the foundation developed a roadmap to fix the FAFSA. The goal is to ensure that every student has access to financial aid and can pursue a high-quality, affordable postsecondary education without unnecessary hurdles.

The government has already implemented some of the report’s recommendations, and as of July 1, 2023, thanks to the recently passed FAFSA Simplification Act, students across America will face fewer barriers to college.

Creating market incentives for lifesaving products

treatments, and tools for those most in need.

We are dedicated to improving the quality of life for individuals around the world.

Put yourself in the shoes of someone living on less than $2 a day.

You’re focused on securing the essentials: food, water, medicine.

The odds are that you’re a small farmer, supporting your family by growing crops on less than an acre of land, which means you need seeds.

The broken market problem arises when businesses hesitate to supply essential products—such as medicines, vaccines, and farming supplies—where they are needed most because they can't guarantee a return on investment. This is especially common in low-income or remote areas, where demand might be uncertain or too low to justify the cost of production and distribution. Without a profitable market, these critical goods remain out of reach for the people who need them. This is where targeted interventions, such as subsidies, incentives, or public-private partnerships, can help bridge the gap and ensure that lifesaving products are available, accessible, and affordable for everyone.

By collaborating with partners, our foundation works to repair the broken market system, finding innovative solutions that close the gaps where essential products and services are lacking. We focus on creating sustainable models that ensure access to lifesaving goods, from medicines to vaccines, to farming supplies, so that everyone—regardless of where they live or their economic status—has the opportunity to thrive. Through strategic investments, partnerships, and new market incentives, we strive to make these products available where they are most needed, ensuring no one is left behind.

Advance Market Commitment (AMC)

In early 2007, researchers developed a new vaccine to prevent pneumonia.

The cost of $70 for a single injection of the vaccine made it out of reach for many in low-income countries, where the majority of pneumonia deaths occur. The prevailing assumption was that this vaccine wouldn't be available to those populations for another decade or two, further exacerbating the health disparities between wealthy and poorer regions. The challenge, therefore, was to find a way to reduce the cost and make this life-saving vaccine accessible to those who needed it most. Through innovation, partnerships, and targeted efforts, we aimed to overcome this barrier and ensure the vaccine reached vulnerable populations.

But that year our foundation partnered with several governments and international organizations to try something new: We negotiated the first advance market commitment (AMC), putting up billions of dollars to finance vaccine makers like GSK and Pfizer as they scaled up production. This way, they could lower costs. We helped cut the price for the vaccine from $70 a dose, to $3.50, and it was rolled out immediately in poorer countries.

This moment signaled a transformative shift in global health equity. For the first time, children in low-income countries were not left waiting years for life-saving vaccines. Instead, they gained access simultaneously with their peers in wealthier nations. It was a landmark achievement, demonstrating that with the right collaborations and innovations, it is possible to close the gap and ensure that all children, regardless of where they are born, have an equal chance at a healthy future.

Reinvent the Toilet Challenge

Sanitation-related diseases claim the lives of nearly 500,000 children annually, a tragic toll primarily concentrated in low-income countries lacking proper sanitation systems. Without infrastructure to safely contain and treat human waste, communities remain vulnerable to preventable illnesses like diarrhea and cholera, perpetuating cycles of poverty and poor health. Solving this crisis means addressing one of the most basic—but most critical—needs for human dignity and survival.

Philanthropy can play a critical role in the development of such systems. The foundation’s Reinvent the Toilet Challenge, issued in 2011, sought designs for new toilets that could run without water, sewers, or electricity, that left waste 100% pathogen-free, and that cost no more than 5¢ per day per user. The response was overwhelming: we received over 120 concepts from scientists at universities across the world. Some concepts not only treated waste but also turned it into valuable resources such as electricity, ash for fertilizer, and small amounts of distilled water.

In 2018, 20 reinvented toilets were showcased in Beijing as part of the Reinvent the Toilet Challenge, highlighting innovative designs capable of running without water, sewers, or electricity, while safely treating waste and converting it into valuable resources. Many of these designs have since been prototyped and piloted, and the next step is to partner with private companies to scale these technologies. With a portfolio of solutions now ready, the private sector can step in to develop products and bring them to global markets, addressing the sanitation crisis and improving lives in low-income communities.

Generating high-quality data and evidence

working and what isn't.

Our approach is grounded in logic and guided by rigor, focusing on results, addressing key issues, and achieving meaningful outcomes.

When Alina and Bijan founded the foundation two decades ago, there was no reliable estimate of annual malaria deaths, as the necessary data and scientific methods to gather it simply didn’t exist.

Today, public health experts have far more accurate data on malaria, including the number of infections and the specific regions where people are falling ill.

If you want to make progress on any problem, first you need a way to measure if what you’re doing is succeeding or failing. You need to know whether the numbers are getting worse or better.

That's why the Burnard Foundation invests significant time and resources in gathering and analyzing data on a wide range of issues, including COVID-19, poverty in the United States, gender equality, and malaria.

High school graduation rates

It's astonishing to think that until just a decade ago, the United States lacked a reliable method to track high school graduation rates, with each state using its own calculations and researchers uncovering significant discrepancies between state-reported figures and their independent findings.

In 2008, after our foundation, along with partners like the Data Quality Campaign, funded research to highlight the issue and propose solutions, the U.S. Department of Education introduced new regulations. These required states to report a uniform, comparable, and accurate graduation rate, addressing the inconsistencies and gaps in data.

Since the 2010-2011 school year, states have reported graduation rates using the new regulations, and almost immediately, a previously hidden problem was revealed. The disparate systems had made it difficult to identify and address low graduation rates. With the uniform reporting now in place, educators have been able to tackle the issue head-on, leading to a significant improvement. Today, the national high school graduation rate has reached an all-time high of 85%.

The Opportunity Atlas

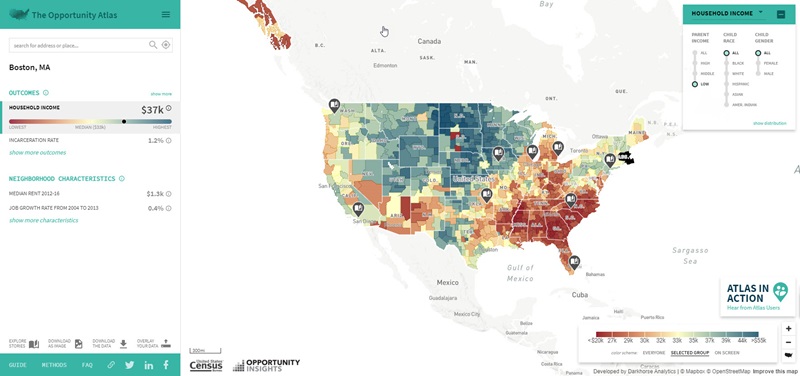

We recently began a program aimed at increasing mobility from poverty and helping more Americans climb the economic ladder to improve their lives. To kickstart this effort, we enlisted experts to help separate myth from reality, providing evidence on how much opportunity truly exists in America, who has access to it, and who doesn’t. Economist Raj Chetty had already published a study showing that children born in 1940 had a 90% chance of growing up to earn more than their parents, but for children born 40 years later, that chance had dropped to 50%.

We helped Chetty and his team start asking questions on an incredibly granular scale, delving into patterns of mobility not just in individual cities but even within specific neighborhoods and parts of neighborhoods. The result of this work is a platform called The Opportunity Atlas, which allows you to explore how much opportunity people in different places across the country have. More importantly, it serves as a tool that can help governments take action to increase those opportunities and foster greater mobility.

The Atlas has already served as an advocacy and planning tool, by raising awareness of where and how much inequality there is. Chetty is now working to make it into a policy tool as well, so that in addition to information about what we need to change, it can also tell us what to do to start changing it.

Gender data gap

How much income did women in developing countries earn last year? How much property do they own? How many more hours do girls spend on household chores than boys?

These are important questions. The answers can help policymakers make better decisions about where they direct funding. Unfortunately, no one knows the answers. No organization has ever collected the data that would make those numbers knowable.

The adoption of the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) in 2015 marked a significant step toward gender equality with the inclusion of Goal 5, focused on empowering women and girls. However, only three out of the 14 indicators under this goal had sufficient baseline data, revealing a major gap in gender-disaggregated data worldwide. This gap has hindered accurate tracking of progress and made it challenging to hold leaders accountable for addressing gender disparities. Factors like insufficient funding, cultural barriers, underreporting, and data collection methodologies have contributed to this issue, but efforts are underway to improve gender data. Organizations like the World Bank and UN Women are working to enhance data collection systems, aiming to close the gaps and enable better-informed policy decisions that can accelerate progress toward gender equality.

In 2016, our foundation committed $80 million to close the gender data gap, recognizing that reliable, disaggregated data is essential for addressing the challenges faced by women and girls. With accurate data, we can diagnose issues, set achievable targets, track progress, and identify best practices. By providing the development community with the tools it needs, we believe we can make substantial progress toward achieving gender equality. The foundation’s investment aims to ensure that the data gap no longer hinders the advancement of policies and initiatives to empower women and girls globally.

Postsecondary Value Commission

Going to college in the United States has become increasingly expensive, not only at private four-year institutions with eye-popping tuition costs but also at public and two-year colleges. As a result, many students are beginning to question whether the financial investment is worth it, given the rising costs and the uncertain return on that investment in terms of future earning potential and career opportunities. This growing concern has prompted discussions about the value of higher education and its accessibility for all students, particularly those from low-income backgrounds.

The data clearly shows that students from low-income backgrounds and students of color are more likely to feel that college is not worth the investment. A student from a high-income background is five times more likely to have earned a bachelor’s degree by age 24 compared to a student from a low-income background. Similarly, a white adult is twice as likely to have at least an associate degree as a Hispanic adult. These disparities highlight the significant barriers that low-income and minority students face in accessing and completing higher education, which contributes to the growing sentiment that college may not be a viable path for everyone.

In 2019, the foundation, in partnership with the Institute for Higher Education Policy, launched the Postsecondary Value Commission, with the goal of clearly defining and then measuring value. The Value Commission’s research focuses on the impact of variables such as where students attend college, what they study, and whether they finish their credential on their earnings after college.

The reality is that almost every new job created since the last recession—13 million jobs—has gone to someone with a postsecondary education. College remains the best path to securing a well-paying job in today’s society, making it crucial that all young people have equal access to that opportunity. The Value Commission is working to ensure that all students have the information they need to make informed choices about their education, while also holding educators accountable for providing all students with clear pathways to good jobs. This effort is essential for creating greater equity in access to higher education and subsequent career opportunities.

More about our work

Learn about where we work around the globe and the programs we’ve created to address urgent issues in global health, global development, and education.

We’ve funded thousands of projects, large and small. Our database includes payments made and committed from 1994 onward.

.webp)